Touchy-Feely: The Return of Tactility

At the risk of dating myself, before everyone had a touchscreen phone, they had cell phones with physical keys. Some had miniature QWERTY keyboards, but most used a predictive typing system called T9, which allowed you to text using a 3x4 numeric keyboard.

Back in high school, one of my best friends mastered the art of T9 texting because he loved to text in class.

He could text one-handed, under the table, without looking at his phone, using a 3x4 numeric keyboard, and even while answering a teacher’s question with a straight face.

It was a miracle to behold.

He could do this, of course, because of the tactile interface his Nokia phone had. The subtle peaks and valleys that his fingertips had come to know by touch and by memory.

With over 3000 touch receptors on each fingertip, they are one of the most sensitive parts of your body. That makes them perfect for navigating physical interfaces where you can easily distinguish between one control and another, even when the distinction is very subtle.

Try it for yourself. Close your eyes and touch a few things around you. You might be surprised at how acutely you feel the subtle differences in texture and even the tiniest bump.

In the past two decades, since the popularization of smart phones, tactile interfaces are becoming rarer and rarer.

Instead of rich experiences of achieving fluency of control through touch, we are converging on a single unifying tactile experience - mashing your finger against cold, hard, glass.

In sci-fi movies, a common visual trope is to see everything controlled via massive panes of intelligent glass. All tactile controls are gone and everything is a smooth, multi-touch surface.

It’s our vision of an advanced, technological future.

But did anyone stop to think about how much that would actually suck?

Touch screens ate tactility

The popularization of touch screen phones in the late 2000s meant that everyone had daily experience with using touch screens. Soon, if your product had a touch screen, it seemed more advanced. More high-tech.

The explosion in supply of cheap, high-quality touch screens from the demand of cell phone production meant that there were now a lot of choices for designers and manufacturers to integrate with their products.

Very quickly, everything started to have a touch screen: printers, speakers, remotes, coffee makers, you-name-it.

Today touch screens are so common that I’m sure most people have had the experience of encountering a display, trying to poke and swipe at it only to realize it’s NOT a touch screen.

Now, there are a lot of good reasons to use touch screens in products: they can display rich graphics and media, they’re highly flexible, responsive, and can provide context-specific interfaces.

For a manufacturer, there are significant design benefits in that you can continue to update the interface over time, and you can lock the hardware much more quickly in the development process and save cost on not having to produce, integrate, and stock spare parts on buttons, knobs, and dials.

But that’s not to say touch screens are a silver bullet solution to all your usability problems. A lot of times, they’re not. They lack any real tactile definition, which can make it hard for users to navigate them without paying close attention, leading to anything from common frustration to real safety risks.

Their flexibility and update-ability can actually be a frustration to users in that it’s an ever-changing landscape you have to familiarize yourself with. A physical interface never changes the location of and icons on all your buttons and dials.

The proliferation of touch screens across consumer products has at least in part been driven by what one technology writer calls “solutionism”, which he describes as “an intellectual pathology that recognizes problems as problems based on just one criterion: whether they are “solvable” with a nice and clean technological solution at our disposal.”

Basically, touch screens are everywhere because they exist and are neat (but often lazy) solutions to whatever usability problem is in front of us.

A touch screen can be integrated and the interface figured out later and iterated upon over countless cycles, even after the product ships. A physical interface demands that a designer truly understand the usability issues and iterate over many physical prototypes and testing cycles before the product design is locked.

It’s no surprise that more and more manufacturers are slapping a touch screen on their products.

Tactility for usability

Tactile controls have a few major usability benefits over touch screens.

Firstly, they offer analog feedback. When you press a button or turn a knob, your fingers immediately sense whether your action was registered or how much you’ve adjusted the control.

Yes, some touch screen devices have haptic feedback, but I’ve yet to see an implementation that even remotely approaches the intuitive experience of getting direct, analog feedback from a physical control.

Another major benefit is that you can fly blind. Anyone who has learned to touch type or play a musical instrument will have had this experience. With a tactile, physical interface, you can use your sense of touch and muscle memory to develop a very close linkage between your brain and the interface, leading to the interface almost melting away.

With the many more physical degrees of freedom available to the designer such as different forms, textures, colors, and the ability to place controls in three-dimensional space, tactile interfaces can also be designed to be very specifically tailored to the nuances of their use case.

You can see this most clearly in professional tools and interfaces. Professionals want to develop that mind-muscle connection and familiarity that compounds their efficiency. Their tools most likely involve physical controls even though most of their functions could theoretically be replaced by a touch screen.

In our own design world, one example that comes to mind are these wacky 3D mice:

Look at all those buttons and that giant joystick!

Touch screens are great general interfaces with an advantage of ultimate flexibility. But when you’re trying to get real work done, it’s gotta be physical.

Tactility for safety

Being able to navigate by touch and basically fly blind has real benefits in dangerous situations where taking your attention away from your primary task could mean the difference of life or death.

And what’s the most dangerous thing that most Americans do every single day?

They get in their car.

A Lifewire article I read while researching this post says, “Neale Kinnear, TRL’s head of behavioral science, reported that ‘taking your eyes off the road for two seconds can double the risk of having a crash, yet a driver can spend up to 20 seconds looking at a touchscreen to perform a simple task.’”

That makes the issue of tactile vs. touch screen interfaces in cars a questions of great importance.

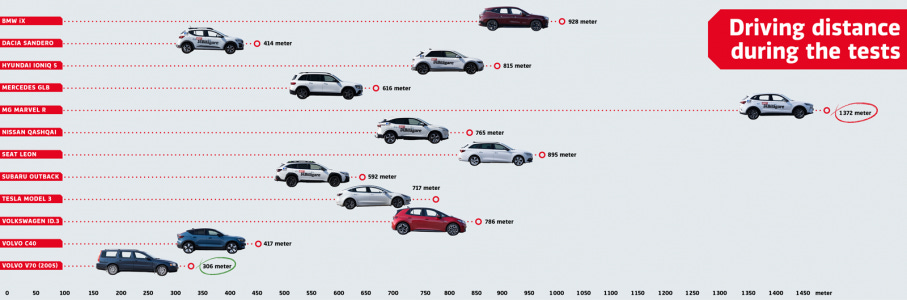

A recent study was conducted by a popular Swedish car magazine where they asked drivers to drive various cars around a track while performing common tasks such as changing the temperature and switching radio stations. They then measured the time taken and distance traveled by the car.

Their findings confirm what we all intuitively know: modern cars (with primarily touch screen controls) performed much worse than older cars with physical controls.

Touch screens first made it into cars in 1986 with the Buick Riviera, which was a car on the cutting edge of technology.

But by 1990, it had been scrapped.

For the same reason we’re somehow rediscovering only now: it was unsafe.

Early adopters, “protested that taking their eyes off the road and their hands off the steering wheel to prod a screen in order to raise the cabin temperature by a few degrees was uselessly and dangerously distracting.” (digitaltrends.com).

The proliferation of touch screens in cars is largely a result of many of the factors mentioned already in this post: consumer expectations, technology looking for problems to “solve”, and a benefit of flexibility and cost to the manufacturer.

Touch screens can certainly have a place in cars. They’re good for things like navigation and other complex functions that maybe don’t need to be accessed while driving.

But do these new touch screen cars perform any of their core functions (other than driving) better than an older car with physical controls?

No.

As one New York Times writer put it, “Touch Screens in Cars Solve a Problem We Didn’t Have”.

Tactility for delight

Some of my favorite designs ever come from a company called Monome.

They’re simple, highly tactile devices for making music.

They sell for hundreds of dollars and they’re constantly sold out. They’re just minimal grids of buttons and knobs.

But that’s all they need to be.

Because buttons and knobs are really, really fun.

There’s no denying it. We love to fiddle with things. You can see it in how children play with their toys (or anything they can get their hands on), poking and tweaking and twiddling the parts.

There’s a real delight to a really nicely designed button or hefty knob that you just can’t get from a touch screen. And that’s an important design consideration in itself.

Think of your favorite object, and I’m willing to bet part of why you like it is because you enjoy the way it feels in your hand. How the controls move (if it has any). The textures and sensations.

Tactility is a core part of how we experience products, and a touch screen doesn’t come close to providing that same satisfaction.

The return of tactile interfaces

If you look around the world today, you might be surprised to find that there is a resurging interest in analog devices - record players, film cameras, tape decks. Things that people thought were long obsolete that younger generations have taken an interest in.

I think this is in part due to our interactions with the world around us being more and more centered around soulless pieces of electric glass. People yearn for something they can touch and feel. They don’t want to just interact with sterile glass panes all day.

That resurging interest has resulted in new products being created in old categories that apply modern digital conveniences and aesthetics to your parents or grandparents tech. There are probably more record players and typewriters in people’s homes today than there were when they were first popularized.

People want to get away from screens.

I think what we’re seeing is a course correction from the touch screen dominated era and a slight return to tactile interfaces, for all their benefits described above.

But don’t take my word for it.

Jony Ive was recently quoted as saying, “But we do remain physical beings. I think, potentially, the pendulum may swing a little to have interfaces and products that will take more time and are more engaged physically.”

I think he’s right.

So before you slap a touch screen on your next design concept, think about whether it’s really the right solution, and whether some good old-fashioned buttons might do the trick.

P.S. Welcome to the 45 new subscribers since my last post! Thank you for reading. If you aren't subscribed yet, consider dropping your email in the box below to get new posts in your inbox.

P.P.S. This is the first post on the new site. Older posts will be migrated over soon. If you're looking for any of my previous posts, you can find them here.